It happens without fail – we are discussing a travel memory with our children and we’re rhyming off the name of the city, people we met with, a park or public space we spent time in, and we’re met with blank stares. Now that they’re older, this is usually accompanied with a, “Nope! No clue what you are talking about,” with the requisite eye roll. Then we remind them about the ice cream they ate, how they fell into a cactus while scooting (yes that did happen in Venice Beach), or some other seemingly insignificant moment and we see the light bulb go on. We used to think this was a Bruntlett family quirk, especially when it comes to food, being unabashed foodies. Turns out, however, our kids are just being kids!

Relationship is in the details

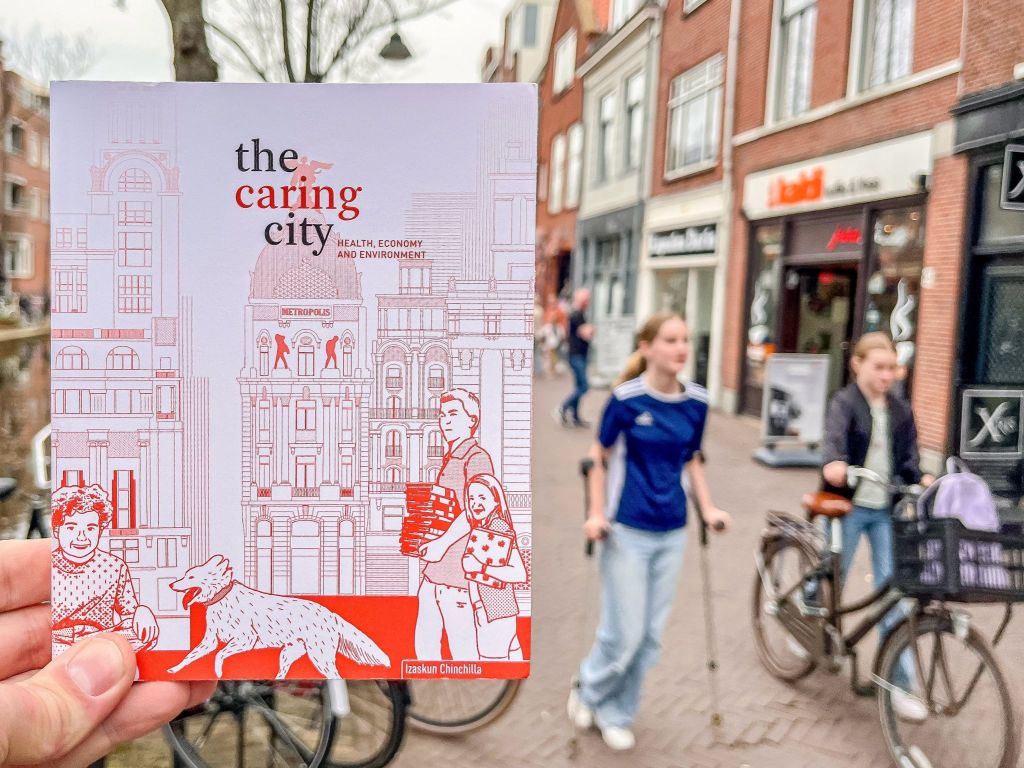

The her book, The Caring City, Izaskun Chinchilla explores how traditonal notions of architectural and urban design have disregarded the role of care in how we live our daily lives within planning decisions. This has led to places that not only meet the daily needs of carers and underserved communities. The places where people live are often disassociated from how people understand their city. A primary focus on (economic) productivity has completely undermined the value of our encounters in public space and our perceptions of our relationship to place. While this impacts us all, we can see this much more acutely in the experiences of children.

Our memories of a place are intrinsicly linked to the experiences we have in them, particularly for children. Up until the age of 14, how we understand the world around us is linked to the moments we have in them moreso that the built environment around us. It’s why we remind our children about what they ate in a place more often then the details of a place. Like, when visitng friends in Montreal, we remind them of stopping at that small pizza place and then walking to the independent creamery that had ice cream “hot dogs” rather than gush about the open streets event happening around them. Chinchilla also emphasises in her book that children form connections with physical spaces that are more detailed or ornate – think a mosaic detail of a facade, or street art – over more monochromatic modern design that favours clean lines and neutral colours.

What this means for our cities

In the urban planning profession, we spend a lot of time focused on the technical elements of a project. Elements like foot or cycle path widths and minimum widths for traffic lanes, the height and slope of kerbs, minimum parking requirements and so on are given top priority. These guidances are of course important to the safety, form, and function of public space, however their implementation shouldn’t be at the expense of making spaces memorable. The addition of a diversity of plants and trees, colour – applied in three dimension, varying textures, and structures that inspire play can help create an experience that sticks with and is attractive for users of all ages and abilities.

As Chinchilla points out, for children – and I would argue many adults as well – the physical spaces along a journey begin merging into a single memory rather that a series of individual ones. Keeping this fact in mind when planning and desgning, for example, a school street and safe route to school could be the difference between the success and failue of the project. If it fails to inspire enough children and carers to walk or cycle to school because it is not inviting, thus creating a lack of experience, then the ultimate goal will be missed. At a time when so many of us are working to facilitate a return of independence and freedom to children, shouldn’t generating places that create memorable experiences for them be a vital ingredient to whatever solution we develop? Even better, let’s let them help decide what an attractive way to school looks like!

The Experience is Everything

As we age, our cognitive ability to recognise more elements of the places we move through increases. Once we are 14, we start to remember street names, and can more easily navigate maps, while also remembering more of the architectural differences of the buildings and structures along the way. We should never minimise, however, that our experience of a place is everything, and the more positive it is, the more likely we are to return. Boring facades, empty public squares void of trees and plants, a lack of variety, fails to establish a meaningful connection for users. Think of one of your favourite cities, towns, or places. I’m sure many physical elements come to mind, but when asked to explain why you find it so attractive, you will more than likely start describing a memory of a special time spent there.

For me, one of those places in Montréal, Canada. As my parents’ birthplace, I’ve been forming memories in that city since before I could walk that have become part of my core understanding of the place. Walking under the canopy of the old trees with my grandmother in NDG on the way to the Metro to go downtown, following the alleyways in Point Ste. Charles to reach the corner store by my Nanny and Papa’s house with my siblings to buy snacks we could never fiund in Ontario, and the countless hours spent cycling with Chris and our friends in the summer sunshine over the last two decades in Le Plateau and Mile End as the cycling network keeps expanding. I may not remember all the street names, but the experiences are integral to my strong connection to the city.

Design manuals and engineering standards are vital for transforming our cities to welcoming places for everyone. But they can’t account for the elements that will generate a memory that keeps people coming back. Only with an integrated approach that brings together practitioners across disciplines to collaborate, complimented by participation and co-creation with the communities where we’re working, can we truly begin to see outcomes that enhance not just safety and design, but also our experiences.

Leave a comment